Monday, December 27, 2004

De Kooning - Late Works 3

|

|  |

| 'Untitled', (Seated woman on bench), 1966 - 1967, Charcoal on Canvas, 28 x 24 in. |

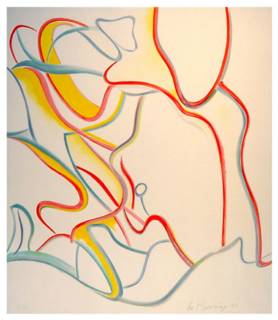

| 'no title', Oil on canvas, 1986, 80 x 70 in. |

- As an aging artist de Kooning would have found it very difficult to let drawing go from his daily habits, it being essential to his make up. Having been throughout his life an adherent of abstract expressionism and 'Automatic' drawing which is supposed to draw from the physical a subconscious response to form and space. It allies the artist very closely with the work physically, cutting off analytical mind functioning somewhat, and relying more upon intuitive or automatic responses to the work in progress. De Kooning relied on his drawing as a basis to his work all through his life. He drew every day (I think from life, even through his abstract work) and the habit of drawing, I think, was very important to his thought process in his work. He relied upon it and during the late work it is the drawing that comes to the fore and out goes the gestural painterliness of earlier work.

I think Kooning's drawing was a physical process that was equally a 'mental' process. This was part of what the 'action painters' of the abstract expressionist movement were trying to explain and was part of the justification for what they were trying to do. Using drawing and painting techniques originating with the Surrealists.

The whole adventure for the abstact expressionists and Surrealists was to discover what the mind was capable of. Drawing upon the unconscious and finding a wealth of information albeit not easily understood due to not being consciously thought of first.

Because of his daily drawing activity de Kooning would have had an enormous back catalogue of drawings on which to refer for his later works. Looking at these and using them as underpainting for his late works in the direct way that he seemed to, must have enabled him to carry on and remember, intuitively, what he was doing. These intuitive marks and lines are learned through years of study and habitual repetition. What is fascinating about de Koonings late works is the reduction to just these elements. Somehow making the decision to leave out or take out so much from the work while bringing or revealing new things to challenge the imagination. Is this decision intuitive, Automatic, conscious? A direct result of Alzheimer's (an expression of the condition)? Probably all of these together. This is an area of the unconscious that we don't know much about.

De Kooning - Late Works 2

|

| |

| 'Untitled V11' 1985 | 'Untitled' 1987 |

- If we were all to get hold of an encyclopaedia or dictionary and look up the various medical terms for dysfunction and mental illness in society we would probably quickly come to some drastic conclusion as to our own personal mental health and the health of people around us: the whole world is 'mad'!. Through history certain words such as mental, idiot, fool, crazy, nuts etc. have been used in everyday language to express our fears of the encroachment of Mental illness. Recently Psychologists have sought to assuage our fears by analysing mental illness and inventing new more accurate and consumer friendly terms for the various varieties of Mental illness, many of which we suffer from at some time or another at differing levels of intensity, in order to treat it. The old simplistic divisions between 'Madness and civilisation' are still lingering ideas in modern times but lie underneath the multi layers of new terms developed for a more refined view to reflect the complicated nature of the mind. If in doubt though or in moments of rash emotion people still resort to primitive fears, to a time when people with mental illness were cast out of 'civilized' society. Alzheimer's was discovered relatively recently, If de Kooning had been painting in the 19th instead of the 20th Century people would not have recognised his condition and his late work would not have been given the kind of informed support that it does today. Also today it is known that by the age of 85 at least 40% of us will have Alzheimer's, and with a growing older population probably a larger percentage in the future.

A thought occurs to me: what if de Koonings late work were more expressive and gestural than his earlier work instead of more linear and non gestural as it is. Would critics have the same problem with it. Would it fit in with the traditional idea of the expressive artist? Certain Abstract artists did draw upon the idea of art as gestural and about sub-conscious communication between body and mind, the paintbrush following the intuitive urges. Has de Kooning stepped out of the boundaries of this relationship with the art audience. The self proclaimed gestural abstractionist turns cool and distant. He now stands back from his work instead of standing close by the large canvas, 'inside the painting'.

De Kooning - Late Works 1

De Kooning 1976

De Kooning 1985

-The following are excerpts relating to the Late works of Willem De Kooning. Those works contrasting so much in style from ealier paintings that they have sparked various debates as to the authenticity of the work. De Kooning suffering from Alzheimers desease during the last ten years of life.

- de Kooning was very much helped by his former wife coming back to live with him during the last ten years of his life and during the onset of Alzheimer's.

She gave order to his day to day life and enabled him to carry on painting while still being able to maintain his memory of earlier works with the aid of constant reference to previous drawings. This may have caused him to rely more heavily on his former drawings and hence the more graphic and less painterly quality to his later work. He used transparencies of early drawings and sometimes laid them over the canvas in order to work directly from them. Elaine de Kooning was important in instructing assistants in the day to day practical matters of preparing canvases and making sure Willem was free to continue his art even through the increasingly difficult circumstances.

Stripping his paintings of the overtly abstract expressionist style reveals the structures that underly his work in more transparent way. However because art critics and collectors had invested heavily in the familiar emotional and expressive language of the earlier work, this work is somehow 'not de Kooning'. The facts are that the work is de Koonings, but de Kooning with Alzheimer's disease. This brings into the equation stereotypes labelled on people with disability and what that means in relation to their art output. De Kooning is one of the few well known artists to have developed a definite disability during his life. This gives us the unique situation where we can analyse the art worlds attitude to disabled artists.

The restriction in his ability to draw upon all of the complexity of skills that he had developed during a long life painting one could see as limiting the work and would accompany a deep sense of loss of a central character in the Abstract expressionist movement and the upsurge of American painting in the 40's and 50's. However I think that quite the opposite is true. The late change in emphasis in de Koonings' work has brought a founder member of the abstract expressionism to the fore again. This new and challenging work, apart from showing a different area of complexity to de Koonings' work, one which brings his work closer to artists such as Brice Marden and his old friend Philip Guston, again, as in the early agenda of abstract artists, deals with issues of conciousness and psychology but in an unexpected way. How conscious was de Kooning of what he was doing? Has that improved or lessened the 'greatness' of his art work or his identity as an artist? How much of creativity includes conscious thought? As in everything is in art the answers are always subjective. -